THE ROLE OF BRAND IN SERVICE FIRMS: THE EVIDENCE FROM ELITE TIER PROFESSIONAL SERVICES IN THE UK

The objective of this qualitative research paper was to analyze how elite tier ‘professional services firms (PSFs) in the UK manage their brands. The paper focused on the four categories of PSF which are accounting, executive search, law and strategy consulting. There has been very little academic analysis of the issue, compared to many other business topics, so there is great attraction in researching such a subject in a constructive fashion. The evidence suggests that the competitive pressures on the professional service industries show no sign of easing. PSFs’ client and employee markets are becoming increasingly powerful. PSFs’ leaders are recognizing the need to create better differentiation, and communicate that differentiation both internally and externally. However, the direction of external forces means that PSFs will need to work harder to create differentiation, thereby making themselves more attractive to both labour and client markets. Some recommendations are highlighted based on helping firms achieve their brand strategy objective, of creating and communicating a differentiated market proposition to attract and retain appropriate talent and clients.

INTRODUCTION

The PSF markets are highly dynamic and have witnessed significant growth in the last 20 years. Global revenue across PSFs grew from $107 billion in 1980 to $911 billion in 2000; equivalent to a staggering 11% compound annual growth rate observed Lorsch and Tierney (2002). Globalization has enabled PSFs to follow their clients into new countries, and to provide new services. This trend has accelerated with the rapid economic emergence of the BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India and China) economies in the last 10 years. In addition, the internet technology has created huge opportunity for firms, both in terms of their ability to provide advise to clients, and by way of leveraging technology to increase the efficiency of their own internal operations. The net result is, that many of the leading PSFs are much more global than they used to be. The job of branding PSFs is more complex, than branding either consumer services companies or consumer goods companies. From the client’s perspective, purchasing a service from a PSF will have considerable commercial ramifications. In the PSF environment, the only real competitive resource that the firm has is its people. Therefore, the PSF brand has two key objectives, to attract and retain the appropriate human resources, and the right clients. Furthermore, because the PSF’s product is its people, the firm’s partners and executives become the embodiment of the firm’s brand; and the fundamental critical task is to attract and retain clients by delivering value added services.

METHODOLOGY

This study adopts interpretive philosophy with an inductive research approach. To fulfill the research objectives, qualitative data has been collected from following two sources;

Primary Sources

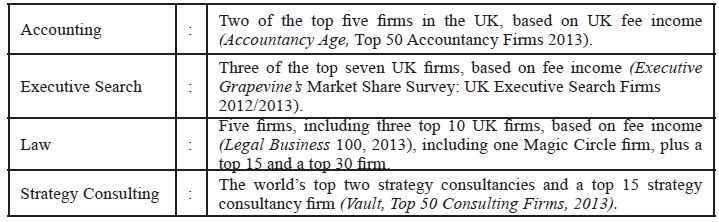

Primary research was based on a series of qualitative one-to-one interview with executive,s responsible for branding and marketing from 13 elite tier professional services firms. The firms interviewed were as follows:

Four long term purchasers of services from firms in the above categories, plus one leading global branding consultancy firm were also interviewed. The interviews focused on the respondent’s criteria for purchasing from

PSFs, and the key challenges that they felt PSFs face today. The purchasers were: (a) The Co-Chairman of a national UK recruitment firm and ex Chairman and CEO of a multi billion Euro global recruitment company; (b) The CEO of a leading UK outsourcing company and (c) The CFO of a multi billion Euro global oil and gas company.

Secondary Source

The secondary research consisted of two elements; a review of existing literature related to the topic and an analysis of associated contemporary information based on academic research papers. Given the lack of work in the area, the paper reviewed two key models Maister’s (1982) Balanced Professional Service Firm Model and DeLong, Gabarro, and Lees (2007) Integrated Leadership Model; to assess how branding a PSF is different from branding a consumer services firm or a consumer products firm. Parasuraman, Zeithaml, and Berry’s (1985) Gap model was also analyzed to find out the need for PSFs to differentiate themselves within their marketplaces, to attract and retain talents and their clients.

Objectives of the Study

• The study is aimed to achieve the following specific objectives:

• To assess how branding a Professional Services Firm (PSF) is different

from branding a consumer services firm or a consumer products

firm.

• To analyze how elite tier PSFs in the UK manage their brands.

• To develop a set of recommendations to help firms to successfully implement

their brand strategy and communicate a differentiated market

proposition; to attract and retain the appropriate talent and clients.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Professional Services Branding

There are distinct differences between branding a product and branding a service. Young (2005a) wrote, that a product company can create a product brand with its own market presence, and that the product’s corporate

owner can have little relevance to real buyers. Examples of such scenarios would be the Persil and Pringle brands made by Unilever and Procter & Gamble, respectively. Berry (2000) and Santos-Vijande, del Rio-Lanza,

Suarez-Alvarez, and Diaz-Martin (2013) reveal, that branding plays a critical role in services companies, because strong brands increase the client’s trust in the invisible purchase and enable customers to better visualize

and understand intangible products. By conducting a research Berry (1999) found, that brand cultivation was a principal success driver in a study of 14 mature, high-performance service companies across a range of industries. Clearlyas Berry (1999) postulated, that the critical differentiator between service- based businesses and products-based businesses is, that human performance rather than machine performance plays the key role in determining the brand. The quality of human performance determines the success of the services business. However, branding in professional services is considerably more complex than branding in consumer services. This is partly because of the difference between the commercial value and implications of a transaction between a consumer service firm and its customer, and a PSF and its client (Berry, 2000). From the client’s perspective, purchasing a service from a PSF will have considerable commercial ramifications. As a result of this dynamic, clients face the issue of having to “surrender to the PSF” and, therefore, unconsciously seek emotional reassurance from the firm (Young, 2005b). This comes by way of the firm’s experience and the client’s interaction with the firm, through the client’s perception of the firm’s brand essence, or by a combination of the two (Young, 2007a).

Maister’s Balanced Professional Service Firm Model

To understand PSF brand issues, it is crucial to review the uniqueness of the fundamental PSF business model. Maister’s (1982) work is the most informative starting point. Maister articulated that the particular challenge

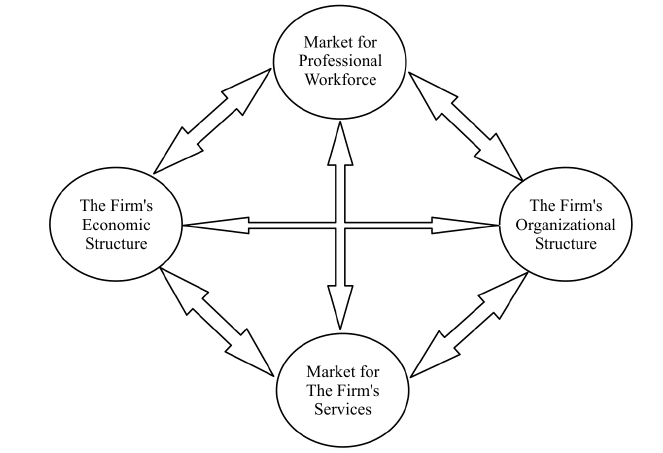

the PSF faced was competing in two critical markets at the same time; the “output” market for services (clients) and the “input” market for productive resources (human resources). Indeed, he argued that the PSF as being “the ultimate embodiment of that familiar phrase, “our assets are our people” stated Maister (1993). From a branding perspective, Maister’s (1982) hypothesis could be translated into the view, that the ultimate objective of the PSF brand is to generate gravitational pull to attract and retain target clients and to attract and retain the best talent. To advise PSFs on managing their client and talent markets, Maister developed the Balancing the Professional Service Firm Model (Figure-1). His key proposition was that the demands of PSFs’ clients and talent markets could be balanced by the firm’s economic and organizational structures. There are four elements in the model which are closely integrated, any change in one element would impact one or more of the other elements. Maister’s model was groundbreaking and has major relevance to branding PSFs today.

Figure 1: Maister’s Balancing the PSF Model

Maister (1982) argued that the classic structure of a PSF firm is based on three levels of professional: the junior (work), manager (minder of work), and senior (finder of work); and the challenge for PSFs is to establish a balance between the types of work performed by each rank of professional, and the numbers of professionals required at each level. On the other hand Maister (1992) observed, that the team structure is a fundamental driver for PSF profitability, because revenue is generated by the hourly billing rate, and as rates are higher for seniors than for juniors, there is a central imbalance in PSFs between the hours billed per level of professional, versus the compensation received . A key strategy PSFs use to lower their costs, therefore, is to leverage more junior professionals.

Maister (1982) also postulated that the interplay between the PSF’s organizational structure and its career structure (i.e., amount of time spent at each level and the probability of being promoted to the next stage) are the key inputs into the firm’s target growth rate. If the firm grows at the wrong rate it will have an imbalance of professionals at each level, which will have a major negative impact in the quality of services provided to clients. To manage fast growth, Maister (1993) suggests that PSFs have four options: improve their hiring process so that more juniors get promoted, improve training for the same reason, increase lateral hires, or change the professional mix within the firm.

In Maister’s (1982) model the key component that links the firm’s markets its clients and its talent is the quality of the labor that the firm needs and can access. Furthermore, the kind of work that a firm does is critical to being able to attract the right talent. He addresses three types of PSF work, based on the degree of the customization of services: Brains,

Grey Hair, and Procedure. Brains projects are based on highly complex work that is probably at the frontier of knowledge and therefore requires a bespoke approach essentially, developing “new solutions to new problems”.

For this reason, leverage (the ratio of junior to senior employees within a firm) is normally low. Grey Hair work also requires significant customization, but not to the extent of a Brains project. This is because other clients will have faced similar problems before. The PSF therefore sells its experience, as well as its analytical capability. Grey Hair projects tend to be more leveraged than Brains projects. Procedure projects are the most leveraged of the three types of work, as the issue that the client needs solved is relatively commonplace and well understood by the PSF, and can

therefore be dealt with by a greater weighting of more junior staff.

The Integrated Leadership Model

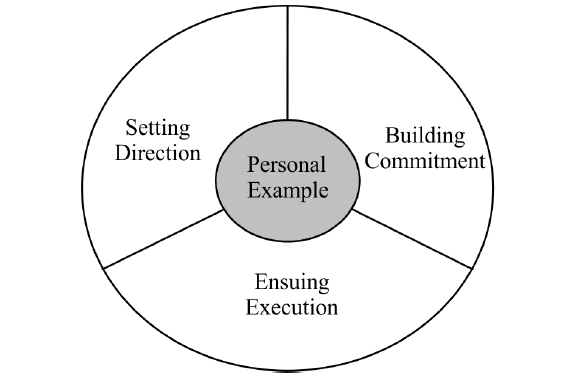

DeLong et al (2007) built on Maister (1982) with their “Integrated Leadership Model” (Figure 2)’. They felt that the strategic dynamics of the professional services industries had developed such, that an updated way of viewing the PSF and the issues related to attracting and retaining the right clients and the right human resources, whether new market entrants or lateral hires, was required. In particular, they felt that the increasing commoditization of services provided by PSFs, and their reaction to that commoditization, meant that Maister’s division of practice by Procedural,

Grey Hair and Brain, termed Rocket Scientist by DeLong et al. needed updating. Other macro factors also drove their decision to develop the new model, in particular, increasingly demanding clients and an intensifying pressure around the issue of talent attraction and retention. These two key dynamic drivers will be analyzed later using Porter’s (2008) Five Forces Competition Model. DeLong et al. (2007) developed their model following, extensive observation of what they believed to be effective and ineffective amongst leaders in a wide range of PSFs. Their work has clear implications for the development of PSF brands. Firms must understand the external forces shaping their industries, and the evolving shape of the competitive landscape. They shouldthen use that knowledge to realign and

communicate their own strategic position and competitive advantage, to sustain the appropriate client and human resources mix and pipeline Delong et al. (2007).

Spectrum of Types of Practice

The integrated Leadership Model propogated by DeLong et al. (2007) views the primary change in the PSF industry. Maister’s (1982) observations werewas that the Procedures segment had split into two large segments, one focused on providing standardized services at low cost, and the other on offering more customized services based on standardized platforms. They believed that the customized segment had broken into Maister’s (1982) Grey Hair category. Similarly, to a certain extent, the former Grey Hair segment had grown into the Brain area by dealing with

more complex, ill-defined issues, while the former Brains sector has had to move further upstream itself to what DeLong et al (2007) describe as “high stakes, state of the art problems”. Their model has four key elements: setting direction, building commitment, ensuring execution, and setting personal example.

Figure 2: DeLong et al. (2007) The Integrated Leadership Model

The model reveals that PSFs must set a clear direction i.e., they tend to focus on completing short term actions at the expense of building and articulating the firm’s longer term strategy. They logically argued that that taking a longer term view “keeps everyone eyeing the same target and minimizes false starts and wasted efforts”. They also question whether a lack of firm wide understanding of the long term strategy may lead some clients to view the firm as being a purely transactional play, and with little if any differentiation from its peers. In addition, linked to the need to set

direction, DeLong et al (2007) argued that PSFs need to work harder to generate commitment from their employees to steer the firm’s strategic direction. Enshrined within this objective is the need to ensure, that the talent that the firm wishes to retain sees that it is highly valued by the firm. This is particularly the case for solid performers says Pawsey (2006), who are not star players and therefore may feel that they do not receive the attention and praise that their star cohorts receive. The third element of the model is about ensuring, that the firm delivers on its promise to clients, not only to generate repeat business from them, but also so that they might act as advocates of the firm to prospective clients. This dynamic works in the opposite direction, as well. If the PSF falls short of client expectations,

the client is likely to tell others within its network states Pawsey (2006), thereby damaging the reputation of the PSF and reducing the opportunity for the firm to generate business from those organizations. The fourth point in DeLong et al’s (2007) model is that leaders must practice what they preach; they must set a culture of leading by example. They must “embody the firm’s stated values and goals or those values and goals become meaningless for professionals”. Getting this wrong is a sure route to hemorrhaging the firm’s talent pool and to eventual failure. DeLong et al. (2007) pointed out towards the need to clearly position PSFs’ leaders, often managing partners, as the firm’s ultimate brand ambassadors and the embodiment of the firm’s culture.

Sustaining Brand Behaviour

Other commentators have analyzed DeLong et al (2007) execution point in relation to PSFs articulating and maintaining consistency of their service quality as core to their brand proposition to maintain and develop

existing client relationships. Young (2005b) argued that clients pay greater attention to PSFs’ service delivery than to their technical capability because technical excellence is expected and viewed as a hygiene factor.

Many firms, however, fail to heed this point, and focus solely on technical excellence. Young (2005b) suggests that service issues that clients are concerned about include work being done on time, the availability and responsiveness of the team, and its client management systems. Young (2005b) articulates one of the key benefits of high quality service delivery as being to stimulate the demand-pull of clients acting as advocates for the PSF’s business.

Pringle and Gordon (2001) elaborate on the concept of service delivery with their idea of “brand manners” to analyze the way in which organizations manage their promises to their clients and to ensure that they are happily surprised as often as possible. Pringle and Gordon (2001) argued that manners occur in every encounter between the client and the firm and that each experience involves four different dimensions that need to be carefully managed: the rational experience what goes on; the emotional experience how the client feels; the political experience why it is right for the client; and the spiritual experience where it leads the client to. Their work is based on showing how firms can create a service culture that can consistently exceed client expectations by all client facing employees “living the brand proposition”. Young (2007a) also reveals that the emotional and spiritual element to the value of the client’s brand experience. He says that what starts as simple reassurance about the quality of service consistency

develops into a deeper but difficult to measure emotional bond the client feels with the firm.

The Need for Differentiation

The increasingly commoditized nature of the PSF markets points to the need for PSFs to differentiate their brands, and to communicate that differentiation in order to build their talent and client bases. An added driver to differentiate is the inherent intangibility of PSFs which makes comparing suppliers even more challenging than comparing suppliers in other industries articulate Lorsch and Tierney(2002). Indeed, DeLong et al (2007) state that creating and communicating a clear point of difference is the only way that a PSF can outperform its rivals on a sustained basis.

Other academic work demonstrates that brand differentiation is one of the most important sources of competitive advantage for businesses in general, propogated by Aaker and Joachimsthaler (2012) and Pearce and Robinson, (2003). Furthermore, research of 6,000 companies by the PA Consulting Group, a management consultancy, showed that competitive differentiation has on average 2.86 times more impact on economic profit than operational efficiency observed Fisk (2003).

The highly crowded professional services markets, however, make creating and demonstrating differentiation difficult. Lorsch and Tierney (2002) pointed out that barring patent protection or monopolistic power, most PSF firm strategies can eventually be copied and most competitive advantages are temporary at best. Research by First Counsel (2007), a legal services consultancy, illustrates the extent of the problem in the legal market. The consultancy’s analysis of perceptions of law firm service delivery and differentiation showed, that 67% of legal service buyers thought that law firms were poorly differentiated from one another. Leiter (2004) provides practical recommendations for building differentiation.

He says that it should be based around the firm defining the positioning theme(s) that resonate at the intersection of opportunity (what clients need and want), capability (what the firm can confidently deliver to clients) and desire (where partners/leaders wish to focus their careers). Leiter (2004) proposes that the positioning theme can be developed in many different ways, including through positioning expert knowledge, client-service delivery, or where firms wish to operate in the services value chain.

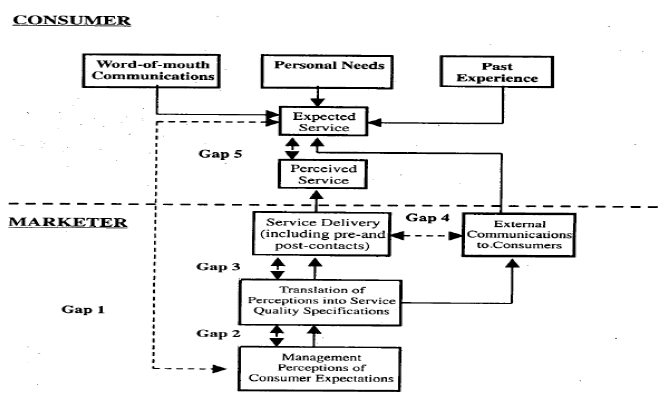

Parasuraman, et al’s Gap Model

One of the strategic tools that PSFs can use to help build their brand differentiation is the Gap Analysis model, illustrated by Parasuraman, et al. in 1985 (Figure 3). The key objective of the model is to understand the gap between the firm’s view and the client and market’s view, from the following five dimensions:

• The management perception gap: the difference between management’s

views of the firm and that of the market;

• The quality specification gap: the difference between the firm’s stated

quality standards and those perceived by the market;

• The service delivery gap: the difference between the firm’s stated service

standards to clients and those perceived by clients;

• The market communications gap: the difference between the persuasive

messages the firm communicates to the market and its service

delivering those messages; The perceived service gap: the difference between the service deliveries

perceived or experienced by clients and their expectations.

Figure 3: Parasuraman, et al’s (1985) Gap Model

Communicating Brand Differentiation to Build Brand Reputation

Having established the firm’s brand differentiators, PSFs must communicate them both internally and externally. However, the inseparability of the production and consumption of professional services, however means that, when it comes to external communications, every individual that interacts with a current or prospective client or employee is an ambassador for the firm’s brand state Laing and McKee, (1998). PSFs must therefore develop integrative, cross-functional marketing cultures embracing their entire organizations. Leiter (2004) agrees with the logical argument of Laing and McKee (1998). He argues that PSFs must think of their professional staff, from their juniors to their senior partners, as integral to the marketing of the firm; because they are best equipped to position the firm’s

capabilities to the external client and talent markets. However, he argued that, in his experience most professionals from big firms see marketing as “someone else’s responsibility”.

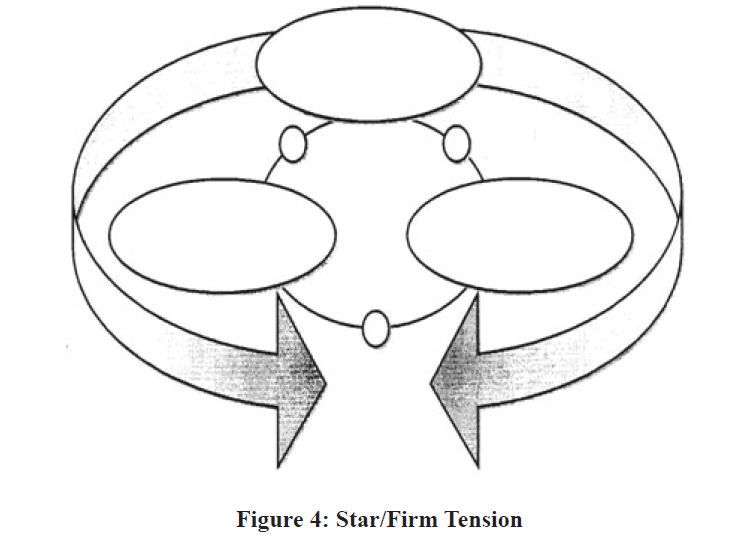

The Partner/Firm Tension

Leiter (2005) analyzes the creative tension within PSF partnerships. Whilst the partnership structure tends to give partners intellectual freedom and entrepreneurial autonomy, by nature, this independence works against the

collaborative efforts generally needed to market the firm and its practice groups. Lorsch and Tierney (2002) reveal that this tension is an inherent characteristic of the PSF business model (Figure 4), whereby executives have to balance their interests with their clients and the demands of the firm. Lorsch and Tierney (2002) also further argued ultimately, it is the behaviour of “stars” in the context of their client and firm relationships, that determines the effectiveness of the firm’s strategy.

Young (2005a) contends that while the brand of the firm and the reputation of key partners become inextricably linked, some partners have become so enamored with their own reputations, that they have discounted the support

of the brand that grew them. He says that there have been examples of partners leaving great firms to set up on their own and finding that they were not as successful as they were before. They discover that their former firm’s brand was a major part of their fee value. Indeed, some new firms have exploited the major brand andbig fee dynamic to build competitive edge.

Contemporary Trends Analysis: Porter’s Five Forces Model

Porter (2008) developed the Five Forces Model (i.e. the power of buyers; the power of suppliers; barriers to new entrants; the threat of substitutes; and the rivalry between existing competitors) as a way of analyzing the

competitiveness of any industry. His model has proved to be an enduring tool for strategic industry analysis remarked Lee, Kim, and Park (2012) and Marshall (2013). In the professional services industries of analysis, all of Porter’s forces, save the threat of substitutes, exert considerable competitive pressure. Furthermore it could be argued that, to some extent, PSFs’ clients themselves act as substitutes for the firm for some activities.

This review will make further analysis of the two key competitive forces that relate to the two core components of PSF brands, i.e. -the increasing power of buyers (clients) and suppliers (talent). It will also look at examples

of new market entrants in professional services, enabled by commoditization.

Increased Power of Buyers (Clients)

Many commentators discussed the increasing power of clients. Leiter (2004) discusses the rapid evolution in client sophistication, thereby dramatically raising the bar for professional performance. Clients have become better trained in their fields stated Leiter (2004) and often have executive education, and international experience . In addition, increasing numbers of clients are likely to have worked in a PSFs and so “know the game”. DeLong et al (2007) also observe that PSFs are being challenged to increase their performance, because clients know more and are therefore

increasingly demanding more and better work in less time. At the same time, DeLong et al (2007) advise, that clients are expecting PSFs to be more transparent in their accountability.

Young (2005b) also reveals that increasingly, clients are tending to want to manage PSFs like commercial vendors. He talks of corporate procurement functions flexing their muscles and challenging previous, informal relationships between PSF’s senior partners and their clients. Van Den Bosch et al. (2005) investigate the growing power of strategy consulting clients. They discuss how consulting firms have imparted knowledge to their clients over a period of time, and the clients have increased their ability to solve their own problems. Patel (2007) asserts that there is a greater inclination for clients to challenge strategy consultant’s invoices, particularly where consulting firms charge fixed monthly fees of £500,000 or more. In the legal market, clients are forcing leading London based firms

to reform their established system of hourly billing, as has been happening in the USA for some time; because they think they are simply paying too much observesPeel (2008). As a result, Law firms are offering their clients alternative charging models and are looking at cost cutting, such as off-shoring more routine services. Peel (2008b) reported that Tim Jones, head of the London office of Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer, said that firms were frequently offering clients deals such as fixed fees or rates tied to the success of transactions. London law firms have also responded to client demands by improving the quality of their service levels. Sherwood (2007) refers to the explosive growth of client relationship managers in UK firms. The executive search market is also facing the pressure of increased client power. In its annual review of the UK search market, the industry’s definitive market analyst, Executive Grapevine, said: “It is clear that clients are willing to shop around for alternative suppliers and don’t

automatically place their business with the largest firms. Indeed, with five new entries into the top 30 this year, there is plenty of room for fresh new challengers.” The report also describes the trend towards the internalization

of searches.

Leiter (2004) further argues that client power has also been growing as a result of an increasing erosion of authentic professionalism within professional services, as PSFs have had to leverage themselves by using more junior staff in order to maintain growth at reduced cost. He postulated, that the result is a substantial gap between what clients expect and what firms deliver. The net impact is that the “average professional client relationship increasingly lacks the fundamental value exchange that revolves around a transfer of expertise”. Clients are therefore demanding either higher impact services or significantly more attractive prices.

Increased Power of Suppliers (Employees)

In 1992 Drucker pronounced: “All organizations now say routinely, ‘People are our greatest asset.’ Yet few practice what they preach, let alone truly believe it. Most still believe what nineteenth-century employers believed: people need us more than we need them. But, in fact, organizations have to market membership as much as they market products and sources and perhaps more.” The tide has turned. In 2006, The Economist dedicated a special report to the war for talent, pointing out that “talent has become the world’s most sought-after commodity” quoted Wooldridge(2006), and Fulmer and Ployhart (2013). Back in 1982, Maister (1993) referred to the retention of middle ranking professionals as being a particularly tough talent management issue, especially for consulting firms. He said that midlevel executives must be compensated appropriately, because their technical knowledge and client experience means that numerous career opportunities outside the PSF are available to them. Today, the balance of power is tilting towards talented employees at more junior levels, as well, and even those who have not yet entered the workplace. Lorsch and Tierney (2002) describe the situation that PSFs face as a war for stars, rather than

a war for talent. The Legal Business magazine (2007) reveals the difficulty of attracting and retaining lawyers at all levels, as being one of the biggest concerns for management throughout the UK’s top 100 law firms by revenue. Peel (2008a) wrote of an exodus of young lawyers into banking and other industries in recent years, due to the excessive long hours culture in law firms and the opportunity to earn more elsewhere. Each year, a significant number of non-partner lawyers leave some of Britain’s top 10 law firms. Peel (2008c) elucidated that it seemed as if rapidly rising salaries for junior , had had little impact on their morale. Employee attrition within accountancy firms is also extremely high observed Perry (2007), as much as 30% amongst the newly qualified and 16% among all staff .

The executive search market is not immune. Anderson (2007) and Moczydlowska (2012) stress about the challenge of recruiting appropriate talent from the market. Donkin (2006) raised the question for search firms operating in the rapidly converging worlds of media and telecommunications, of how they would find their own search executives that fully understand both worlds enough to be able to advise clients. The internet has speeded up the switch of power towards talent, in particular sites such as Vault.com and Legal Weekwiki.com, which enable potential employees to get unauthorized, inside views on firms from current or ex-employees stated Wooldridge (2006). Many commentators talk about the difference in mindset between Generation Y and previous generations. Leiter (2004)

contrasts the current career paths of executives, where they do not wish to stay with the firm for more than a few years, with the dynamics of previous times, where people joined firms as a journey of partnership over 20 years.

However, research by NAS Recruitment, reported in Spectator Business (2008) says, that while Generation Y may not be interested in a long-term career in one firm, the generation does have high and rapid career expectations,

and demands a good quality work-life balance observed authors Lush (2008), Luscombe, Lewis and Biggs (2013). Academic work points to the frustration that PSF partners feel with these new realities. DeLong et al (2007) report that PSF partners say. that the current generation of professionals demand more feedback and more flexibility than prior generations, and that they are less willing to work long hours. Maister (1993) and Lorsch and Mathias (1988) argued. that the sense of irritation partners have about the additional time they have to spend on human resources issues, compared to previous years is predominant. However, according to Lush (2008), the reality is that demographic change means that firms will have to adapt to Generation Y’s perspective more and more. Considering

the situation in Britain, he says that as the country’s 19.1 million baby boomers start to retire, there are only 11.2 million Generation X people to replace them. His hypothesis is, that Generation Y is therefore likely to be

pushed faster to fill the talent gap.

Weakening Barriers to Entry

The desire for better work-life balance is not restricted to Generation Y, more seasoned professionals also demand it. The low barriers to entry in professional services markets has enabled new, niche models of PSF to be developed to cater to these lifestyle demands. Some of these have been very successful at competing against the established, elite PSFs. Maitland (2007) argued on this trend in the Financial Times. She cites Axiom Legal, a law firm staffed by 200 lawyers that hires out experienced lawyers at a third to half the rate of the Magic Circle London law firms, to leading firms such as Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, Cisco and Yahoo. Operating in London, New York and San Francisco, Axiom Legal is able to charge such competitive rates because it has minimal office space, executives tend to work at client offices home and there is no partnership structure. Maitland (2007) refers to Eden Mcllum and Resources Global Professionals, as examples of firms working with similar models in the strategy consulting and accounting sectors.

RESEARCH FINDINGS

PSF View

Branding is becoming more important for PSFs

Research showed that brand owners tend not to be part of the firm’s leadership group, instead they do report to the top teams. Furthermore, there is a consistent message, from across the professional services disciplines reviewed, that the firm’s leaders and partners are increasingly buying into the strategic value of branding for the firm. As one of the accounting firms executive reported, that at the partner level there is a shift in mindset towards understanding the need for centralized brand initiatives. This level of senior engagement is most clearly evidenced by the fact that, 10 of the firms reviewed were either in the process of going through a major strategic brand review for firmwide application, or had been through such an exercise in the last few years. The brand owners report that, in the normal course of business, branding issues are a regular part of the boardroom agenda. “Even before our brand audit, brand issues would be discussed by management on a monthly basis” (Law firm, interviewee 10; 2014). “Brand issues are brought up in board meetings explicitly every other meeting” (Strategy firm, interviewee 12; 2014). “There are no board meetings where brand is not on the agenda in one form or another. We talk a lot about culture and values and these feed very closely into the brand integrity, loyalty and discretion, putting the client first, team second, individual third, and the value of deep knowledge. These are mantras that one hears time and time again – they underpin

everything we do and everything we stand for” (Executive search firm, interviewee 5; 2014).

For some brand owners, it has been a tough battle for them to persuade their firm’s partners and leaders of the value of firm -wide branding initiatives. In particular, this has been the case for those brand owners who have wrestled marketing budget, from partners and put it into their own central budget pool. This dynamic harks back to the central conundrum of the partner firm balance of power, articulated by Lorsch and Tierney (2002).

“It’s about how comfortable partners feel about losing control of some of their marketing budget to a central function. But centralizing budget is the right thing to do” (Accounting firm, interviewee 2; 2014)‘We starved the

partners of resources, so they’ve got no money to go and build their separate divisional brands” (Accounting firm, interviewee 1; 2014).

PSFs are Engaging More on Brand Issues

The key reasons given as catalysts for this greater focus on strategic brand management were, maintaining the appropriate talent base and creating and communicating differentiation. These drivers corroborate with those

outlined earlier in this paper. However, many respondents stressed that controlling their firm’s growth, globally, added pressure to managing these two primary drivers.

Maintaining the Appropriate Human Resource Base

Interviewees referred to brand strategy as critical to attract and retain the right talent to profitably service their clients in a profitable manner. A common theme was the challenge of key junior hires leaving the firm after only

a few years, either when they feel they have received adequate training or professional qualifications, which they can leverage to get a better job elsewhere. A second common challenge was the issue of integrating lateral hires into the firm’s “way of doing things”. Several interviewees spoke of the need to ensure the cultural fit of new hires during recruitment. The respondents’ objective was to minimize the level of firm effort required to instill its brand service propositions into new employees. In terms of attracting and retaining talent through softer issues such as work-life balance initiatives, corporate social responsibility, and health and well-being programmes, there was a feeling that whilst these attributes might have been key differentiators for firms a few years ago, increasingly, they are becoming hygiene factors and a mere “cost of doing business”.“Recruiting the best people and keeping them is an issue because people often join a professional services firm thinking that what they’ll do is get qualified and then leave for industry” (Accounting firm, interviewee 1; 2014). “One of our biggest threats is people diluting the brand promise by making exceptions like “Oh but, I just want to do it this way” or “at my last firm we used to do this and that, it worked really well for me so I’m just going to do that here” (Law firm, interviewee 8; 2014). “We respect people’s work-life balance more than we did before, but I think all organizations are having to do that, just as their housekeeping. We’ve got diversity networks set up but they’re nothing different – they’re just what everybody else is doing, so I wouldn’t purport to say that they’re really innovative. We are doing some quite interesting things in the community because we know that people care about what the firm does there, but again, we’ve had to do it, partly

because our competitors do, And like all firms, we’re putting a lot of effort into a wellness programme” (Accounting firm, interviewee 1; 2014).

Creating and Communicating Differentiation

Almost universally, interviewees said that their firms struggled with creating a genuinely differentiated strategic proposition in order to create sustained interest from star talent, both external and internal, and from current

and potential clients. One brand owner said that professional services firms that share the same category often use the same language to describe themselves, their capabilities and their points of differentiation, when the reality of what the firms do and how they do it can differ considerably. She referred to publicly articulating differentiation almost being pointless, to the extent that it would lead to competitive firms replicating the positioning, even if that positioning did not reflect reality. A representative from a law firm questioned how far it was possible for law firms to differentiate based on what they do; he said differentiation could only be based on less tangible issues such as firms’ quality of service, and, that, ultimately, raw chemistry between the firm and the potential client probably played a key role in the purchasing process. Several respondents also articulated the particular challenge of benefiting from being part of an elite club brand, such as the Magic Circle of law firms, or the Big Four accounting firms, because it enabled them to charge a premium. However, they said that, at the same time, they needed

to create some form of differentiation from the other members of the club. One law firm executive said that he thought that, on the whole, there was very little differentiation between the Magic Circle firms, but that he understood that several of those firms were seriously thinking about how they needed to differentiate. Many interviewees also spoke of the difficulty of communicating differentiation internally, not only to strengthen

employees’ bonds with their own firms, but also to equip them to communicate that differentiated proposition to the outside market. “You look at the consulting industry – there is not a lot of differentiation out there” (Strategy consulting firm, interviewee 11; 2014). “We see ourselves’ as consultants, but everybody calls themselves consultants” (Executive search firm, interviewee 5; 2014). “The biggest personal challenge for me is trying to be and say something different in a field that is quite homogeneous.” (Accounting firm, interviewee 1; 2014). “When the CEO joined the firm, he very quickly started articulating the fact that we don’t differentiate ourselves enough from the other executive search firms. If you look at the way our peers describe themselves, it’s all very similar” (Executive

search firm, interviewee 3; 2014). “How do you differentiate a service? Fundamentally, the quality of legal advice is given. How do you buy a service when you get down to the last three or four on your list – they’re all broadly similar, they’re all good quality, the ball park prices are the same. It gets down to the less tangible things. What do I feel it’s going to be like working with them, what supporting services will they provide, how are you going to review and manage the relationships?” (Law firm, interviewee 10; 2014).

Managing Firm Growth

PSFs reported that both of the above issues are exacerbated by challenges, related to managing their firm’s further growth. Firms have benefited through globalization in terms of being able to expand the number of geographies in which they work, the types of clients they serve and to some extent, the range of services they offer. However, a flipside of this growth has been the challenge of recruiting the volume of talent, with the appropriate technical capability and cultural fit. A second issue has been ensuring that thetalent engaged is able to service clients according to the firm’s brand values, and to communicate the firm’s differentiation externally.

This can be particularly problematic for those firms, that have to hire thousands of people each year. This applies even more so for firms that have been expanding rapidly into emerging markets, especially to match the fast growth of their clients in China and India in recent years. Intuitively given the slow down in the global economy, it could be expected that managing growth in emerging markets would ease off. Many respondents, however, expect this challenge to intensify in the coming years. “There is the issue of ensuring that the 10,000 people that work for us deliver the right experience to our clients” (Accounting firm, interviewee 1; 2014). “Increasingly our clients are global in their aspirations and we have to follow them. So a principle threat for us is maintaining consistency of high quality work and service levels across the network” (Law firm, interviewee 7; 2014). “Ensuring that clients across the world have a consistent view of us is another challenge in the whole re-branding initiative” (Strategy consulting firm interviewee 11; 2014). “At about 40% and 60% compound growth in the last few years, our growth rates in China and India have been too high. Given that our business is defined by the quality of our people, you just can’t find the right number of people in these countries. We’ve been trying hard to get our growth down to 20 to 25% in China, but it’s been challenging because client demand has been so high. Our consultants have to be able to work anywhere in the world. So a consultant from our China office would have to be capable of operating in New York, if we decided that’s where they needed to be…that’s the hiring criteria” (Strategy consulting firm, interviewee 13; 2014).

Psfs Are Giving More Emphasis On Internal Brand Communications

PSFs are investing considerable effort in communicating the essence of their brands and their brand service propositions internally. This is to generate greater buy in into the firm’s strategy from the employees,so that

they can be effective brand ambassadors for their firms. To do much of this work, there is an ever closer union between firm’s brand owners and the human resource function. Many firms are investing significant attention

on new employees. A respondent from an executive search firm said, that a core part his firm’s on- boarding strategy for new hires is, to interview them to understand their pre-existing perceptions of their new employer, in terms of what it does and how it does it. A law firm reported that, it found that the most effective way for the firm to communicate its brand proposition to trainees was to involve them in the firm’s marketing campaigns from day one. Another law firm spoke of introducing its graduate recruits to the importance of branding and marketing in law, even before they start work at the firm. The firm implements this by sending its trainees to speak to their graduates on their campuses. An accounting firm said that when it launched an advertising campaign, it expended huge effort

on internally engaging its people, to explain to them what the messaging behind the campaign was, so that they bought it and were proud of it. One of the most progressive internal branding strategies reported was by a law firm, which incorporates employee adherence to the firm’s brand messaging into its evaluation system. “We’ve spent a lot of time looking at an induction programme to communicate our key messages and to educate people about where we are going” (Law firm, interviewee 7; 2014). “We are paying increasing attention to our brand in our induction and assimilation programmes. We’re also piloting a system of assimilation for people who’ve been here for two years, as a way of embedding them further into the organization and making sure that they are as effective as they can be.

This obviously requires careful nurturing” (Executive search firm, interviewee 5; 2014). “Integrating branding with our training programmes is very big for us. In fact, we start this process with new graduate recruits even before they join the firm” (Law firm, interviewee 9; 2014).

Firms Believe They Are Effective at Monitoring Their Brand Service Propositions

The interviews conducted with the PSFs for this paper indicate that, to date executive search firms and strategy consultancies have been better at measuring their client’s satisfaction levels than accounting or law firms. However, the findings suggest that client satisfaction measurement is an area that all firms, including accounting and law practices, are taking seriously day by day. There is a range of methodologies in place, with firms often using a blend of informal dinners between partners and clients and in-depth third party interviews with clients. Interviewee 4 (Executive Search Firm) said that “We have done client satisfaction surveys for a very long time. For 85 to 90% of the searches that we conduct, we have a third party who goes to the client and spends anything from twenty minutes

to forty minutes on the phone with them going through a template of questions such as how the search was conducted, the process, and the quality of the candidates. We get pretty good feedback from these, which we analyze on a regular basis across the board nationally, by practice, by geography, you name it. So we’re constantly feeding information about ourselves back into our best practice committees and, of course, we monitor very carefully by consultant how well they’re doing on the basis of these client satisfaction surveys” (Executive search firm, interviewee 4; 2014). On the other hand interviewee 2 of Accounting firm (2014) said that “we measure our customer’s satisfaction in much more depth than we did before. This includes independent interviews. The test for us is the referral question – would a client refer us to another company? That metric is being measured and benchmarked continuously by office, by service line, and by market area. We’ve been doing this now for about a year”.

Thought-Leadership Is The Most Effective Tool For External Communication

In terms of communicating the essence of their brand to potential clients and recruits without exception, firms said that the most effective method is direct partner engagement. Firms said that key forum for communication are seminars, where partners have an official speaking slot and more informal networking situations such as dinners and other events. Beyond the personal touch, PSFs use a range of tools to communicate their brands to external stakeholders. However, firm’s’ singled out thought leadership research based papers, as the most effective of these tools. Firms use these papers to communicate their new knowledge or point of view to stakeholders, primarily by mailing the papers directly to their desks or by email, and by running simultaneous public relations campaigns in order to leverage the third party endorsement of influential media groups. In some cases, firms also host their thought leadership papers on their website, and build seminar programmes around the content of the papers. Several firms spoke of using thought leadership campaigns as a strategic way to build awareness of the firm, in areas in which it was not normally associated. Others viewed thought leadership as so important, that managing the production of papers is embedded within the reward and remuneration structure of the firm.

The importance that interviewees attach to thought leadership papers is reflected in Leiter’s (2004) recent “Nine Ps of Professional Services Marketing”, where he says that to succeed in today’s environment PSFs need to adopt a publishing mindset. “Our intellectual capital program is very focused on publications and getting those out to people. It’s another opportunity for our name to cross their desk and have them see that we are addressing and working on issues that are relevant to their business. Getting third party endorsement of our publications through the media

also gives great reach and visibility about a subject that could be of interest to clients around the world” (Strategy consulting firm, interviewee 11; 2014). Again interviewee 9 (2014) of Law Firm said that “we benefit from thought leadership initiatives in several ways. In the first instance, when the questions are asked, we get awareness even if people don’t respond. This is particularly valuable when your name isn’t normally associated with the category or issue that you might be researching. We’ve benefited in the capital markets area in this way. You also get awareness through mailing the document and from press coverage. If you do a piece of research on a regular basis, perhaps annually or bi-annually, you can really take ownership of an area. So, over time, thought leadership can help

leverage you up the food chain in areas where you are not necessarily renowned”. Furthermore, interviewee 5 (2014) of Executive Search Firm postulated that “We spend a lot of time and resource on producing thought leadership publications. It gives clients and candidates an opportunity to talk to us in a way they wouldn’t talk to anybody else about what’s happening in their industry”.

View from an Accounting Firm

An accounting firm interviewed provides a progressive example, of the way in which some PSFs are incorporating traditional consumer brand communications tools into their branding strategies. Indeed, the interviewee believes that her firm’s strategy is reflective of the potential transformation of professional services marketing. As well as doing straightforward display advertising in national and regional press, the firm has used outdoors advertising to target affluent commuters into London, and into the firm’s important regional centres. Currently, the firm is in the process of rolling out a display advertising campaign at major international airports, backed up by strategic online advertising, in order to attract executives from the large global companies that the firm is targeting for business. In

the UK, the firm is planning an integrated campaign with the Financial Times. The campaign will involve sponsoring a supplement in the paper about issues core to the firm’s business, followed by a seminar, an on line discussion page, and podcasts. The firm will also have a “roadblock” on the Financial Times website the day the advertising launches, which means that the firm will own all the pop-up advertisements on the paper’s website for one hour. Finally, all subscribers to the paper in Greater London will receive their paper with a firm branded wrapper on the day of the

campaign launch. Using demographic analysis to better understand the consumers of particular media outlets, has been central to the firm’s decisionmaking about which media to use and when. Interviewee 1 (2014) of an Accounting Firm said that “Using demographics in professional services marketing is really changing. It started in the US but it is very much coming over here. As an example of what we’re doing, we’re looking at using drive time radio for commuters in some of the regions where it is very powerful, but not in London, where drive time radio has less impact on our target segments.”

Firm’s Brand Owners Still Face Major Challenges

Whilst the evidence from the interviews demonstrates that PSF’s partners and leaders increasingly recognize the benefits of clearly managed brand strategies, there remain many tough issues for brand owners and marketers

to overcome.

Thought Leadership Overload

The inevitable result of more and more firms using thought leadership papers as a cornerstone of positioning strategy is, increased competition for the attention of the intended recipients. There is a sense of information

overload. Many interviewees reported this problem, and Young (2007) refers to 10,000 white papers being produced on a monthly basis by the full range of PSFs. The mass distribution capability of e-mail has exacerbated the situation. A second issue is the question of how much of the material propagated as thought leadership really is new thinking, rather than thinly veiled sales collateral stated Leiter (2005). Indeed, many of the interviewees admitted that their thought leadership papers varied in quality and said that they are working to address the problem. A particular issue highlighted by one strategy firm was, that the speed of business change today made it very difficult to provide really valuable insight into a market and for the material produced to stay topical. As a result of this dynamic, this firm

is overhauling its publishing function and its entire digital presence. The same firm also reported the need to leverage other organization’s knowledge bases such as academic institutions and think tanks, to embed greater

value into the creation of thought leadership initiatives, whether in paper form, or by way of seminar discussions on the topics of analysis.

The branding consultancy executive interviewed highlighted the firm versus partner issue when he said, that a key challenge for firms when producing thought leadership material is ensuring that the firm’s brand benefits as much as the paper’s authors. “We are really trying to get away from doing thought leadership for the sake of it. We have been guilty of churning out rambling reports in the past. So we’re trying to get the partners out of that habit” (Executive search firm, interviewee 3, 2014). “Fortunately these days everything that gets published has been through an evaluation process, so there is a reason to everything we produce and an objective in mind” (Executive search firm, interviewee 5; 2014). “The real time effort is in coming up with a concept that’s truly different” (Strategy consulting

firm, interviewee 11, 2014). On the other hand interviewee 1 (2014) of an Accounting Firm said that “We do thought leadership to varying degrees of effectiveness – I challenge how much is actually really leading thought. The other point is that too often partners produce the paper, have the launch dinner, but never actually get round to having the conversation with anybody they don’t’ already know”.

A Gap Between What Psfs Say About Themselves And How Clients Perceive Them

Firms were asked to what extent they believe that clients receive a consistent message about their firm’s brand positioning. PSF interviewees were requested to give a number between one and five, with one being the lowest

score and five being the highest score. Answers ranged from one to four, with the median response being three. Clearly, firms recognize that there is considerable work to do in this area. This finding links back to the difficulty of creating differentiated propositions and communicating them to outside markets, through their people (as well as through other means such as thought leadership), particularly in growing global businesses.

Demonstrating Return on Investment in External Brand Communications is Difficult

This research reveals that across all sectors analyzed, PSF brand owners really struggle with metrics that enable them to clearly demonstrate internally, the return on investment in external brand communications. There are some tools in place in some firms, but they tend to revolve around brand awareness before and after advertising, and press coverage versus peer media footprints. This situation truly reflects Linderman’s (2003) comment “Even though measurement has become the mantra of modern management, it is astonishing how few agreed systems and processes exist to manage the brand asset.”

Interestingly, one strategy consulting firm executive said, that his firm carefully tracks the commercial impact of its major thought leadership papers. This contrasts with a competing firm, whose interviewee said that the consultancy never tries to trace back work to a thought leadership study. He said that his firm viewed its publishing work only for reputation and brand positioning, and to build the skills and capabilities of its consultants. “It’s not a scientific process but we know that some of our significant pieces of annual index based thought leadership pieces have tangibly helped to drive business growth. You can track it very easily; when we put out press releases, we analyze the number of hits that we get on our website, the number of enquiries that we get, and we put a dollar value on the number of engagements that come in through this work” (Strategy consulting firm, interviewee 11, 2014). On the other hand interviewee 13 (2014) of Strategy Consulting Firm reveals that “we gave up any formal evaluation of our brand long ago. We have very strong marketing and brand people but they have never come up with quantitative measurements that we’ve been happy putting any validity in”. “We’re still in a very embryonic stage of developing measurement methodologies” according to a Law Firm (interviewee 7, 2014). “The finance department recently asked me how I should be evaluated, but I wasn’t able to give an answer, so be truthful, I don’t know” (Strategy Consulting Firm, interviewee 12; 2014). “Metrics are a nightmare. I’d be kidding you if I said “oh it’s gone up from

this to this and we’ve done that” (Law firm, interviewee 10, 2014).

Partners and Leaders Are Not Completely On Board

In spite of the fact that partners and leaders increasingly get the value of strategic branding as noted earlier, there is still much work brand owners need to do to persuade their firms of the value of brand communication. Many firms spoke about the inherent issue within PSFs of balancing the firm’s interests with individual partner’s interests. The branding consultant interviewed said, that in his firm’s experience of working with many leading global PSFs, partners are so used to focusing on their own issues and ways of working that they struggle to see how conforming to stipulated brand service standards is progressive, or why they should invest in non-billable branding work like writing hought leadership papers. Indeed, many partners still have a residual view, that internal brand resources are

little more than cost centres and a drain on the firm’s profitability. One publicly listed executive search firm interviewee spoke of her CFO’s sole focus on meeting quarterly earnings targets to the exclusion of all else, including

the potential long term value to be gained from investing in brand initiatives. One law firm interviewee said that it was easy to get funding for internal brand communications, but that he had to really fight to get funding for an external campaign. Interestingly, there was a view from some interviewees that partners already existing in the firm, make more effective brand owners than career branding and marketing executives. They felt that because the partner fully understands the culture and dynamics of the firm and has practitioner experience, he or she has more powers of

persuasion over the firm’s other partners and leaders.

One global search firm executive even said that it had been a major exercise to persuade its partners of the value of presenting the firm’s logo in a consistent way in stationery, presentations and email communication. “Our CFO sees marketing as a huge, huge drain. She doesn’t really get the brand. As we’re a public company, her sole focus is the quarterly numbers and the analysts. She sees everything else as complete frippery around that. Marketing is still trying to make a name for itself in the firm, and the education that goes around the brand is still in very, very early stages in some places. “We’ve had huge allegations of clogging up email in -boxes, so we are cautious with our internal comms” (Executive search firm, interviewee 3; 2014). “Even though brand and brand communications are

brought up quite frequently at senior management level, the trouble is that most of them don’t really understand it, so the conversations tend to be illinformed” (Law firm, interviewee 7; 2014). “I would say one third of the

partnership firmly believe that investing in brand communications is the right way to go. However, another third says “I’m only interested in selling” and has a pretty short term approach, and the final third is agnostic either way” (Strategy firm, interviewee 12; 2014). “Brand activities have to be turned into actionable stuff for partners. If we’re not careful, it just becomes seen as a lot of marketing bullshit” (Law firm, interviewee 10; 2014). “The battle we face is that partners will say “Well, I took them out for lunch and then I got a deal, but what did advertising ever do for me?” (Accounting firm, interviewee 2; 2014). “In accountancy firms, it’s a real “doctor heal yourself” sort of situation – even though these guys are dishing out advice to businesses day in, day out, they can’t see it themselves when it comes to their own business that they should invest in their brand” (Accounting firm, interviewee 2; 2014).

New Media is a Challenge

Just as it was the first to adopt traditional consumer branding techniques, Adams (2008) suggest that Accenture appears to be leading the way in the adoption of new media tools to build its brand to business audiences. The

consultancy has used Web 2.0 and social networking sites like Facebook and Second Life to reach potential recruits, and podcasts as a medium for executives to consume Accenture content when they are travelling. Accenture is now experimenting with using mobile phones in a similar way.

In fact, most of the firms interviewed for this paper are experimenting with various new media tools, in particular blogs. This is especially the case for firms Telecommunications, Technology and Media (TMT) practices. When firms are using blogs, they tend to be for internal communication, rather than for external communication. However, one executive search firm is in the process of releasing its first external blogs through its website. The objective is to use the blogs from a thought leadership perspective. However, none of the firms interviewed suggested, that they were as advanced as Accenture in their utilization of new media techniques to build their brand, and a number of firms spoke about the challenge of maintaining high quality content in their blogs. Questions were raised about how frequently firm blogs should be produced, and how open they should be to additional input from other parties, either internal or external.

Some interviewees were concerned about the potential negative impact of social networking sites on their brands. One strategy consulting firm said that his firm had 5,800 consultants on Facebook and more than 10,000 including alumni, but that with absolutely no governance over the site, it was a potential risk for the firm’s brand reputation. There was a concern shared by several firms that they needed to get better at understanding and leveraging new media, in order to keep pace with Generation Y and future generations. Interviewee 2 (2014) of Executive Search Firm said “We’ve got to change the way we do business to survive. The next generation of talent will be very different to this one. We’re not up on Web 2.0 and the way that people are now interacting with each other. It’s seen as a huge threat in terms of networking and the role that we can provide for clients and candidates. We have a very strong relationship with the World Economic Forum, and we were talking about building an online community with some of those people a kind of high level Facebook. But the reaction internally has been this is not what we’re about, we’re about face-to face.” On the other hand interviewee 10 of a Law Firm (2014) comments that “Blogs are a difficult step. Once you start a blog, you have to make sure you keep it going. Then do you have a moderated one? Do you have

to have it open? Can everyone post?”

Brave Marketers say Invest in Branding in the Downturn

Given that this paper took place during the first significant economic downturn for several years; interviews also covered the extent to which brand owners and marketers saw disproportionate benefits for their firms by increasing investment in brand communications in such an environment. Clearly respondents said that there were many variables that would have an impact on the investment decision, not least from the depth of negative exposure of individual practices to economic decline, and opportunities arising from bearish markets. Nevertheless, there was a sentiment from many interviewees that careful investment could reap benefits that would not normally be associated with a more positive macro- economic environment. “If you’re brave, invest in your branding – because so many other people are going to be pulling back, this is the time you can get the cut through” (Accounting firm, interviewee 2; 2014). “If you spend in a downturn, you can make a bigger impact because there won’t be any distracting noise as other firms will be spending less. In 2008, we didn’t spend a great deal of money, but no one else was spending then. I don’t think anyone had taken full- page adverts in the media we chose at that time. So, we made a big splash. Lots of people were talking about it and we ruffled a few feathers which was good” (Law firm, interviewee 10; 2014). “I think you need to look at the downturn and say let’s make sure that we are building our brand to take advantage of the situation. How you build the brand depends on what those opportunities are. For instance, “you could do some really good PR, which is very cost effective, or build relationships with people through small dinners” (Accounting firm, interviewee 1; 2014).

PURCHASER VIEWS

Initially Partner’s Reputations is more Important than the Firm’s Reputations

Interviews with four senior business executives that had purchased services from PSFs for some years suggested, that their key purchasing criteria is the strength of an existing relationship with a trusted PSF advisor, based on

previous experience of working with that individual, or the recommendation of a trusted colleague or member of the purchaser’s professional network. On the surface, PSF’ brands seemed very much a secondary consideration to the reputation of individual partners. However, two purchasers spoke of hiring consultants from previously unknown strategy firms; but that what got the consultants “through the door” was the credibility they had from previous senior positions at top tier global strategy firms. One CEO also cited the example of investment bank Goldman Sachs having an exemplary process for buying clients into the firm’s brand, rather than into particular individuals. He said that Goldman’s strategy is essentially to make sure that clients are continually introduced to very senior people within

the firm, so that the client has a range of trusted advisors at any one time. The objective of the strategy is to ensure that there is no real threat to the firm client relationship, should one of the senior advisors leave the firm.

Auditors were viewed as a special case, because even if purchasers were not happy with their auditor, it would be extremely difficult to change the provider due to the corporate governance questions and reputation risk issues

that would be raised. “I was recruited through Spencer Stuart, which is why we still use them. A lot of our professional service work is bought based on people senior execs have already worked with” (CFO, interviewee

14; 2014). Again CEO, Interviewee 16 (2014) also comments that “On the search side I’ve used Spencer Stuart quite a lot as they recruited me to a CEO position and one likes to pay them back. On the strategy side, we’ve tended to use McKinsey – again because of personal contacts. It’s all about networking”.

Challenges for PSFs

When asked about the major challenges that PSFs face, the answers were consistent with the views of PSF brand owners,the literature review and the business media journals. The big three problems were demonstrating

differentiation, managing global growth, and balancing the partner-firm conundrum. One respondent said that the single biggest issue was the need for firms to create truly global partnerships, that are able to deliver the same quality of service anywhere in the world. His view was that the challenge was directly proportional to the extent to which the firm’s service is communal. Executive search is the worst PSF sector at delivering a consistent level of service, globally, because it is such an individualistic industry, he said. His proposition was that the networks of auditor partnerships suffer from the same problem to some extent, but that they are more drawn together because of the ramifications of failure. Law firms he felt, were more effective at consistency of delivery, as they are not quite as individual based as accounting or executive search. In his view, investment banking was the industry that best exemplified the provision of a consistent level of service worldwide, as it is very communal work. The driver for this he argued, is the comprehensiveness of advice that is required by clients. He said that a partner in a global investment bank for example, might need to provide advice across all the major capital markets, which would therefore lead to a strong organizational integration of the firm’s systems and people across the world. “Demonstrating differentiation is the biggest issue for professional services firms. The Big Four accountants are basically the same. They are all as good as each other, whichever way they wrap it up” (CFO, interviewee 14; 2014) “We did have a global agreement with Spencer Stuart, but it didn’t make a difference as the partnership structure of the firm meant that it wasn’t very collegiate there didn’t seem to be any real benefit for say a US colleague to help

out a European colleague with a search” (Co-Chairman, interviewee 15; 2014). “Professional services firms are people businesses. The challenge is building brand equity beyond the individual and there is no one way of doing it. Part of brand management is the interplay between the institution and the individual” (CEO, interviewee 16; 2014).

Client Service Reviews

In contrast to what PSF brand owners said, purchasers of professional services do not feel that PSFs are very effective at monitoring their service delivery to their clients. This plays back to Young’s (2005a) point that clients

focus more on the firm’s service delivery than technical capability, because technical excellence is expected as a given, and referring to Pringle and Gordon’s “Brand Manners” model of exceeding client expectations . Based on these interviews, some firms are not getting it right. Clearly, the quality of client service delivery is an area that firms should never take for granted. One interviewee said he did not think any of his PSFs in the categories of analysis officially monitored his view of their service. Another said that only his auditor evaluates his view of its service. Another said that he hears nothing from his auditor or his law firm, both of which are top four firms in their respective industries, but that his strategy consulting firm (Incomplete here?)

RECOMMENDATIONS

On the basis of above analyses some recommendations are given based on helping firms achieve their brand strategy objective, of creating and communicating a differentiated market proposition to attract and retain appropriate talent and clients.

Make Sense of Global Complexity:

PSF clients and potential clients will continue to take advantage of globalization, by expanding worldwide to provide more services to more clients. This will occur in spite of economic

downturns such as that being experienced at the moment. Clients will need solutions for their increasingly complex cross-border problems. This provides opportunity for PSFs to create differentiated brand propositions. By

investing in understanding these problems, developing solutions for them, and then communicating their new capabilities; firms should be able to attract the most appropriate talent, as well as those clients that need their problems solved.

Develop In-depth Understanding of the Competitive Environment:

For sustained client and talent success however, firms will need to ensure that they have in-depth knowledge of their peer capabilities and positioning, as well as their client’s and prospect’s business problems, in order that they might be able to develop those aspects of their businesses that provide real sustained competitive advantage.

Understand Generation Y and Build Career Options for Them:

Clearly Generation Y is not only the future talent pool for PSFs, but also the future client pool. So firms should invest appropriate resources to understand the

generation’s aspirations and motivations. With the evidence suggesting that Generation Y is less employee-loyal than Generation X on the talent side, the challenge is not only attracting the right people to work for the firm in the first place, but also developing genuine career paths so that the best talent stays with the firm for some time, perhaps on the partnership level. Furthermore, it is reasonable to expect that the firm partner tension problem will become more acute, when Generation Y comes to partnership.

Cultivate Alumni Networks:

Some elite tier PSFs are exceptionally good at managing their alumni networks, particularly for the development of new business opportunities and for the referral of other employees. Other firms

could learn from these examples of best practices.

Work More Closely with Human Resources:

Attracting and retaining the appropriate talent base will become an increasingly important job for the PSF brand. Firms should seek ways for their branding and marketing functions,

to work more closely with their human resources departments so that the firm’s brand messages can be delivered more effectively and consistently to the firm’s employees.

Develop High Quality Communications Campaigns:

Communications will be essential to maintain the talent and client mix. Internally, firms must focus on clearly articulating their corporate points of differentiation, and

their service propositions to employees in order that they become effective brand ambassadors and constantly exceed client expectations. This is particularly important for those firms, that have large global employee bases or

are rapidly expanding their headcounts across borders and across cultures.

Leverage New Media:

With advertising investment switching from offline to online media, the balance of media power is shifting online. New firms founded by executives that have grown up in the Internet age, will be well equipped to fully leverage new media tools. Established PSFs that are managed by baby boomers must therefore ensure, that they have the right resources in place to intelligently exploit the opportunities of web-based communication, both internally and externally.

Real Thought Leadership Campaigns:

Being able to help clients make sense of the ever more complex global market place with new and differentiated solutions, will enable PSFs to develop real thought leadership papers.

Brand Owners and Marketers Need to Demonstrate Return on Investment in External Brand Communication:

Part of the reason that brand owners struggle to convince some of the partners and leaders of their firms of what they do, is that they are unable to demonstrate the commercial benefits of some of their external brand communication. Brand and marketing owners should focus on finding tools and metrics for evaluating their work, that clearly resonate internally at the management and partner levels.

Formal Monitoring of Client Services is not an Optional Extra:

Firms must truly understand how clients view their service, including the quality of input from every individual that works for the client. Having an external